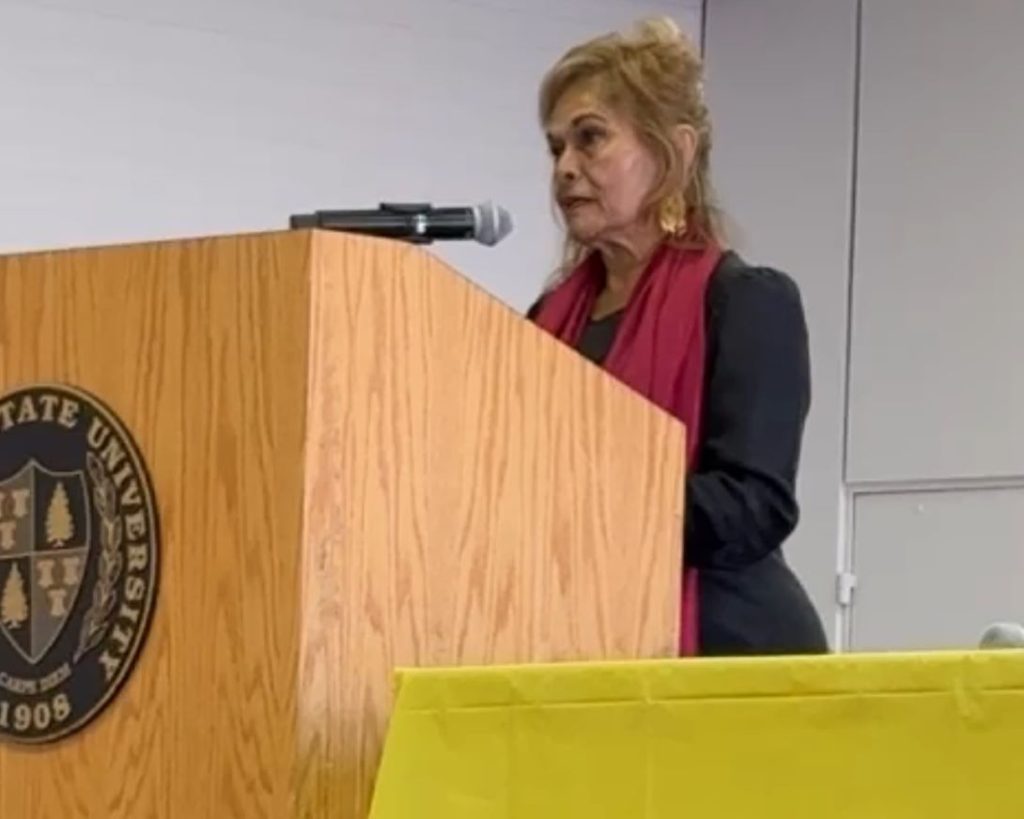

“This is exactly where we need to be,” exclaimed anti-racism activist and conference panelist Spirit Tawfiq as she opened her remarks on Day 1 of the Liberation Based Healing Conference. She was among 30+ speakers, artists and performers who shared their experiences and knowledge with a packed room at Montclair State University on November 3 and 4, 2023.

During a highly charged and politicized time in our history, less than a month after war erupted in the Middle East, the 18th Annual Liberation Based Healing Conference provided a healing space for respectful, authentic dialogue on critical issues including enslavement and genocide, white supremacy, immigration justice, and racial and gender inequality in the workplace. Throughout the two-day event, insightful panel discussions and inspiring performances were followed by periods of reflection and dialogue, allowing the more than 150 attendees to process and share their perspectives.

The conference, founded by Dr. Rhea Almeida, director of the Institute for Family Services, was co-sponsored this year by Montclair State University (Dr. Mayida Zaal and her colleagues), and Tri County Care Management Organization (Deja Amos, James Parauda and Nicole Russo), which supports youths experiencing behavioral, emotional, social, developmental and mental health challenges.

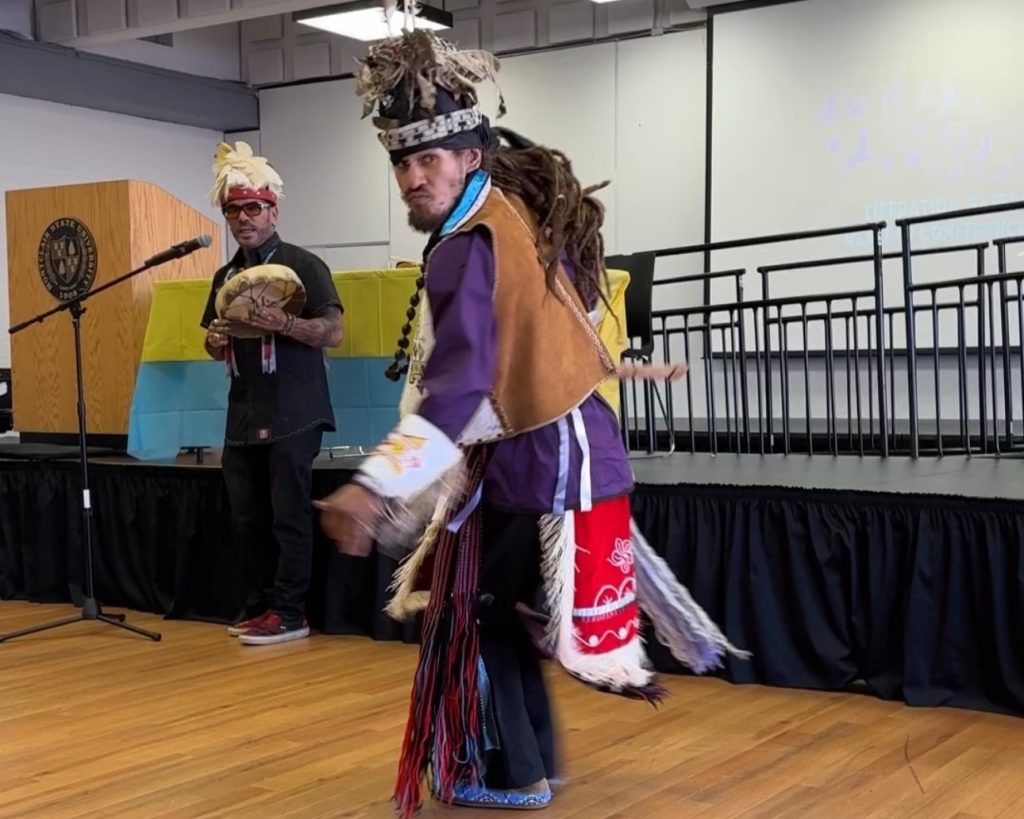

The program opened by honoring the Indigenous land where we convened that day with music and dance provided by members of the Redhawk Native American Arts Council. This was followed by opening remarks by co-hosts Mayida Zaal, MS, PhD, Associate Teaching and Learning Professor at Montclair State University; Rhea Almeida, MS, PhD, LCSW; and Deja Amos, MSW, operations manager at Tri County Care Management Organization. Dr Almeida then provided a brief overview of liberation based healing practices and decolonization as a framework for all that was to follow.

“We usually think about liberatory practices as described, sometimes, as self-care or empowerment practice, but really it comes from the scholarship of anti-oppressive theories and practice, that is where the empowerment pillar comes from,” she explained. “While these are important aspects of well-being, they are not liberation practices.”

The first panel discussion and presentation, “Reparative Voices for the Injuries of Enslavement and Genocide: Unveiling Hidden Narratives of Black Belonging, Community in Appalachia, and the Holocaust,” set the stage for a powerful morning. New Jersey-based musician Avi Wisnia shared stories and songs about his grandfather, who survived the Holocaust by singing to his captors. Clory Jackson, creative activist and founder of the Brownsville Project, then relayed her personal journey being a Black person born and raised in Appalachia.

“I always felt out of place, like I didn’t quite belong. After graduating high school and going to a college far away, I vowed never to go back and I hid my hillbilly drawl,” she recalled. That all changed when she learned that her hometown of Brownsville, Maryland, was once a self-sustaining community for freed Black people before they were displaced to make way for Frostburg State University. Her own grandfather’s home, a house he built, was razed. “We need to examine our past to better plot our future,” she said.

When something profoundly oppressive happens to our descendants, what does it take to make us whole again? she asked. The conversation continued when Spirit Tawfiq introduced her mother, civil rights activist Minnijean Brown-Trickey, who made history as one of the “Little Rock Nine.” Brown-Trickey and eight other African American students resisted opposition to desegregate Little Rock Central High School in 1957.

“Central High was considered one of the most beautiful high schools in America by the American Institute of Architects. It was reserved for white students only, even though it was built in 1927 with both Black and white taxpayer money,” Tawfiq relayed. Segregation prevented Black students from entering the school for decades to come. When Miss Minnijean and the eight other African American students entered the school in 1957, under the protection of the National Guard, they innocently believed that once the other students got to know them, they would like them. “They realized very quickly that was not the case,” noted Tawfiq, who went on to discuss the ways in which they were taunted and traumatized, even physically assaulted.

“There weren’t counselors in those days (to help us through the trauma),” said Brown-Trickey. “You just grinned and bore it. Elizabeth (one of the Little Rock Nine) suffers to this day with PTSD. It is very severe; she still can’t be in a crowd or where there are loud noises. I think the nine of us have different levels of PTSD.

“I was attacked by some girls. They meant to hurt me,” Brown-Trickey recalls. She responded by saying “Leave me alone, white trash” and was expelled. “Yet the ‘N-word’ was used every day, all day, all night,” she continued. “I keep hearing about ‘mob violence,’ and how we are seeing it for the first time. But this is not the first time. We had serious American terrorism happening in 1957,” she stressed.

“We present our history as a fairy tale, and we condition young people to not know (what happened). In Belfast, you could ask people if they know about the Little Rock Nine, and they will say ‘yes.’ In Cape Town, South Africa, they use Little Rock to learn about apartheid. I call this profound intention ignorance, and we are all victims of it.”

Today, Brown-Trickey is committed to peacemaking, environmental issues, developing youth leadership, diversity education, cross-cultural communication, and gender and social justice advocacy. Her highly anticipated participation in the conference was one of many highlights. Said one student in a follow-up survey, “I was honored to be in the presence of Ms. Minnijean Brown-Trickey. Her testimony was powerful, and her vulnerability to share her recognition that she experienced sorrow underneath the anger was profound.”

Throughout the next two days, community activists, scholars, teachers and social workers, as well as students and staff of Montclair State University, heard deeply moving stories and gained perspective on the ways in which our shared traumatic pasts impact our present well-being.

“Our stories are so interconnected,” says Tawfiq. “The power of storytelling is transformative, healing and liberating.”

This is the first in a series of blogs revisiting the 18th Annual Liberation Based Healing Conference. As we begin to prepare for next year’s conference, to be announced in the coming months, we draw upon the many teaching moments we experienced at this year’s conference, which propel us to create positive social change.